The Story of Mankind Part I

The Story of Mankind

The Story of Mankind Part I

The Story of Mankind

The Story of Mankind Part I

The Story of Mankind

The Story of Mankind Part I

The Story of Mankind

Study the lesson for one week.

Over the week:

Activity 1: Narrate the Lesson

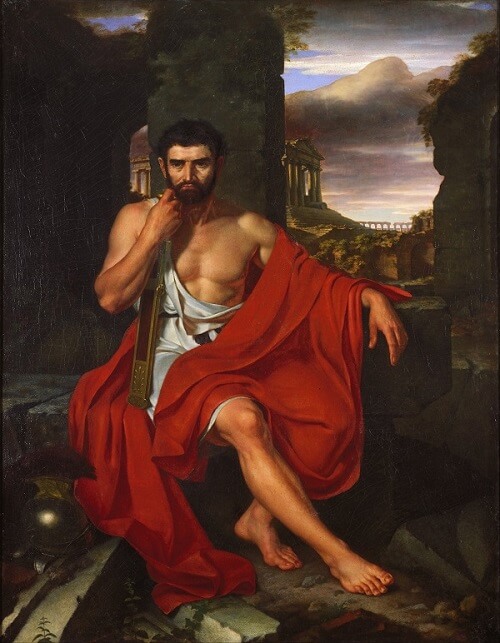

Activity 2: Study the Story Picture

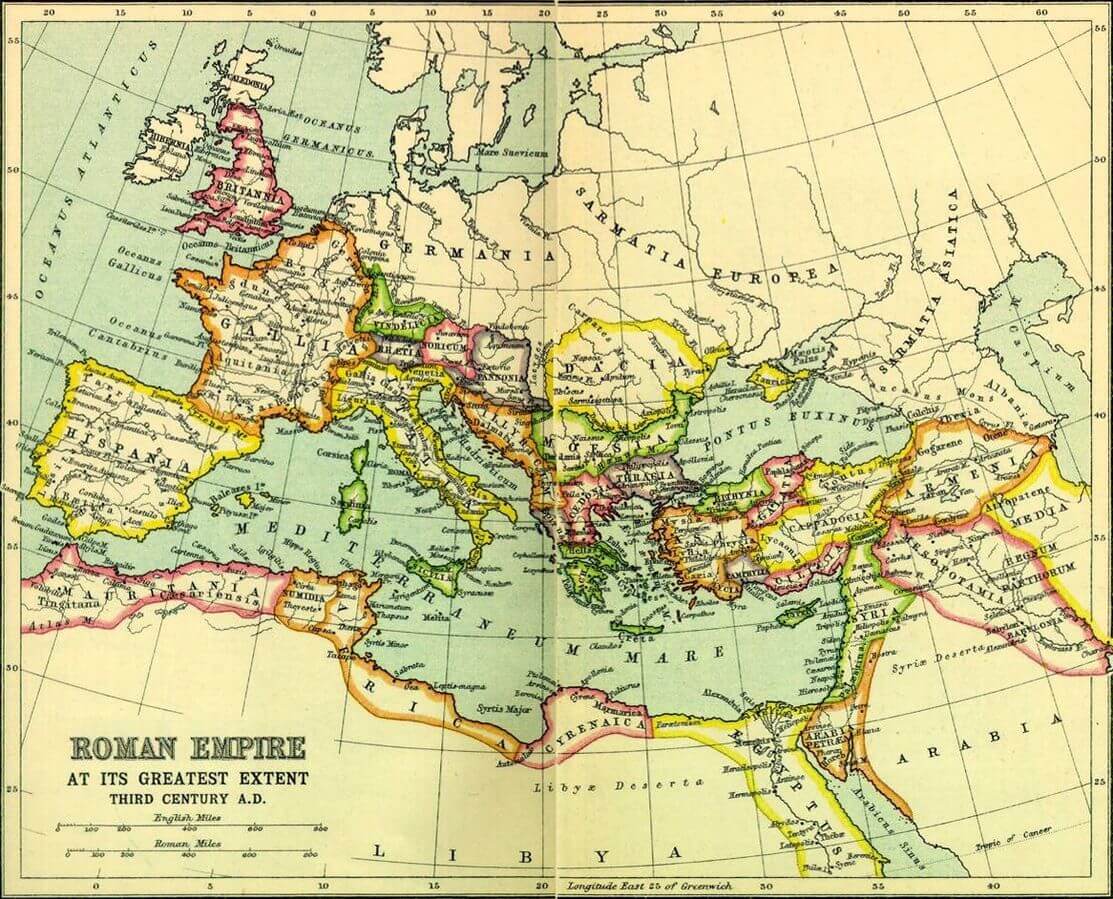

Activity 3: Map the Story

Activity 4: Complete Copywork, Narration, Dictation, and Art

Click the crayon above. Complete pages 55-56 of 'World History Copywork, Narration, Dictation, and Art for Third Grade.'